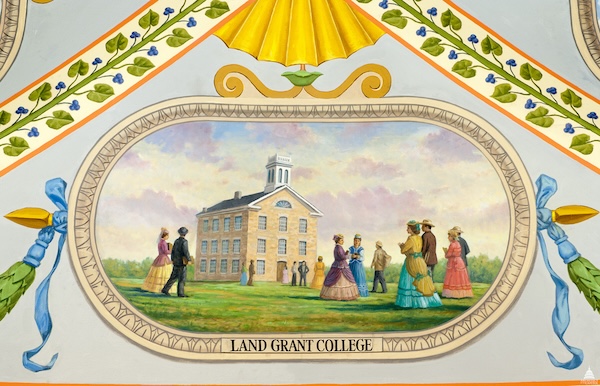

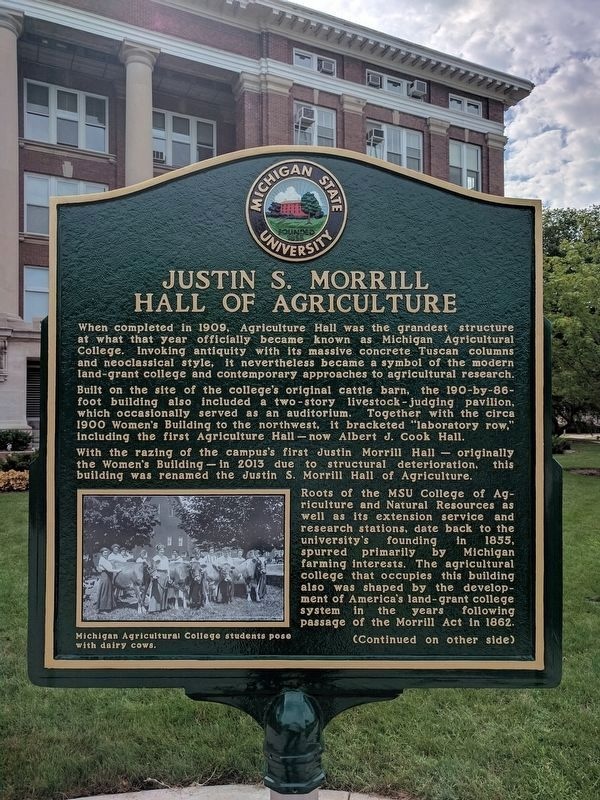

In 1863, Kansas State Agricultural College (now Kansas State University) became the nation’s first operational “land-grant” college. The land-grant college system was established starting with the passage of the Morrill Act in 1862 which was meant to extend higher education to the “industrial class,” or the common person. Because of the land granted to each state and territory to support the establishment of these institutions, the Morrill Act of 1862 became known as the “land-grant act.”

The effort to establish the system was led by Congressman Justin Morrill of Vermont, who believed that a true democracy meant educating everyone, not just those who sought careers in law, politics, and the ministry. Morrill was also influenced by a crisis of declining American agricultural productivity.

For some historical context, the first colleges established in America were to prepare ministers and to educate the upper classes, resulting in early institutions like Harvard in 1638, William and Mary in 1693, Yale in 1701, and Princeton in 1746. By 1860 there were close to 400 colleges in America and nearly all of them were devoted to the liberal arts. Only 3% of these colleges had departments dedicated to science, and the study of agriculture was a rarity.

There had been a growing call for the creation of agricultural colleges for some five decades before the 1862 act was finally passed. At the turn of the century, America’s scientific knowledge of agriculture was nearly nonexistent. Most knowledge was passed down from father to son, There were some farm publications such as the American Farmer newspaper, as well as local journals, where people shared their “knowledge” but the information was often inaccurate. While early agricultural experimentation did occur, it was not organized and received no public support.

Morrill had begun hearing about the advances in scientific agriculture in Europe and believed that similar practices could be applied in the United States, especially as the nation expanded westward. Note that the Morrill Act of 1862 was passed the same year as the first Homestead Act that accelerated the settlement of the western territory.

The law created public colleges where agriculture and mechanical arts were to be taught. The legislation gave federal lands to each state to sell to support the establishment of a college. Each state received 30,000 acres per senator and representative in Congress. If no available public lands were left in the state, land in other states (generally out west) was given to states to sell in the form of “land scrip”. The money generated from the sale of the land was to be invested and the income generated was to support the college.

The Morrill Act was first proposed in 1857, and was passed by Congress in 1859, but it was vetoed by President James Buchanan on the grounds that education should be left to the states. Morrill was also hindered by southerners’ skepticism of the expansion of federal powers and the bill’s perceived favoritism toward northern states and territories. After the Civil War began, Morrill introduced the bill again in 1861 with an amendment that the proposed institutions would teach military tactics as well as engineering and agriculture. Aided by the secession of many states that did not support the plans, the reconfigured Morrill Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862.

Ironically, western states that later benefited from the Morrill Act were some of its loudest detractors in the beginning. Westerners feared that all of the public lands would be taken from their states. Kansas senator James Lane offered an amendment that limited the land claimed in any one state to one million acres, effectively cementing the bill’s passage.

During the Civil War, only two states, Iowa and Kansas, passed land-grant resolutions. The state of Iowa was the first to accept the terms of the Morrill Act which provided the funding boost needed for the fledgling State Agricultural College and Model Farm (eventually renamed Iowa State University of Science and Technology). The first land-grant institution actually created under the Act was Kansas State University, which was established in 1863, followed by University of Nebraska (Lincoln) in 1869.

While the Morrill Act called for the teaching of agriculture and mechanical arts, it did not specifically call for research to be conducted in these areas. To rectify the situation and establish a scientific basis for the subject matter, Congress passed the Hatch Act in 1887. This act established Agricultural Experiment Stations at the land-grant colleges. This legislation actually had two purposes. It called for “scientific investigation and experiment respecting the principles and applications of agricultural science” and it also called for “diffusing among the people of the United States useful and practical information on subjects connected with agriculture.” The provision for diffusing information was designed to show the value of land-grant colleges to the farmers. This provision of the Hatch Act eventually led to the establishment of the Cooperative Extension Service and the teaching of agriculture in the public schools. By the beginning of the new century, scientists throughout the land were at work on agricultural research projects.

There are thousands of examples of the impact from the work undertaken by the land-grant universities. One scientist, Mark Carleton, traveled for the US Department of Agriculture to Russia where he found and imported the rust and drought-resistant winter wheat which now makes up more than half of the United States wheat crop. Other agricultural scientists made equally important contributions over the years. Marion Dorset conquered the devastating “hog cholera,” and George Mohler, the menacing “hoof-and-mouth disease.” From North Africa, one researcher brought back Kaffir corn; from Turkestan, another imported yellow-flowering alfalfa. Luther Burbank in California produced scores of new fruits and vegetables; in Wisconsin, Stephen Babcock invented a test for determining the butter-fat content of milk; at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the great scientist, George Washington Carver found hundreds of new uses for the peanut, the sweet potato, and the soybean.

Now, some 162 years later, this tradition continues across America through the network of 112 land-grant universities that serve students in every state, the District of Columbia, and the five inhabited U.S. territories.