If you live along the original Pony Express trail and see a guy on a horse thundering by with a mail pouch, it (probably) wasn’t a ghost. Some 650 riders are currently participating in the annual National Pony Express Re-Ride, which reenacts the mail delivery service by horseback that briefly ran between Sacramento, California to St. Joseph, Missouri.

The original Pony Express was formed on April 3, 1860 and operated until October 26, 1861. The idea was to create faster mail service to the Pacific Coast, particularly California where the population had boomed following the discovery of gold a decade earlier.

At the time, telegraph service to the West was still at least a year away and railroads only reached as far as the Mississippi. Mail to the West Coast was therefore carried by ship from New York to Panama, where it was taken across the Isthmus of Panama by horseback or rail, and then put aboard ships bound for San Francisco. Under ideal conditions, it could take three or four weeks to reach California. It was also expensive, costing the government more than $700,000 annually while returning little more than $200,000 in postage.

Some mail was also carried by stagecoach by the Overland Mail Company, which used the 2,795-mile “Southern Route” between Tipton, Missouri, and San Francisco. The service promised delivery within 24 days but in reality, it usually took months. One stunning example of how these delays impacted the half-a-million people now living in the West was when California was admitted to the union in 1850 – It was six weeks before the residents of the state learned the news!

Keep in mind, this was all playing out as the US was inching closer to Civil War and there were concerns that the Confederacy would try to disrupt communication between the Federal Government and California, a nonslavery state. Keen to prevent this, Senator William M. Gwin of California proposed an alternate route, known as the “Central Route,” that was 800 miles shorter than the Southern Route and believed to be less at risk from Confederate sabotage.

Gwin tapped a stage express owner, William Russell, to establish the new service. Along with Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell, the three founded the Pony Express. They were expected to operate the service for about a year, which was about how long it was expected to run telegraph service to the West.

Majors was the real force that made the Pony Express a reality. He arranged the purchase of some 400 ponies and oversaw the construction of nearly 200 stations across the uninhabited areas the route would cross. He hired the station masters, arranged the stocking of provisions, and hired the riders. Remarkably, he accomplished all of this within two months.

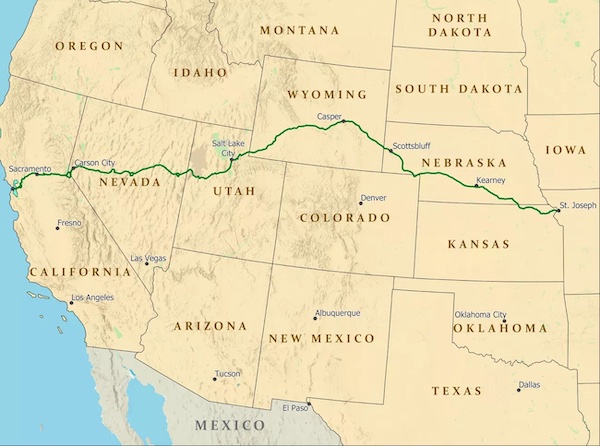

To meet its guarantee of 10-day delivery of mail (letters and newspapers only) from St. Joseph to San Francisco, the company required its horses to be ridden at top speed. The horses, therefore, could not run a great distance and had to be changed every 10–15 miles at the strategically placed relay stations. The route they traversed was over 1,966 miles, stretching across the Kansas plains, into Nebraska, along the Platte River and through the Rockies, into the valley of the Great Salt Lake, across the Nevada deserts, and then over the Sierra Mountains. After finally arriving in the Sacramento Valley, the mail was then carried by steamboat to San Francisco.

About 80 riders in total worked for the Pony Express. They carried the mail in pouches known as “mochila” that could be quickly transferred to a new horse and rider. The price of a letter was $5 at first, and reduced to $1 per half-ounce by July 1, 1861. During its 18 months of operation, the incredibly efficient service lost only one bag of mail.

The riders faced incredible dangers from harsh weather, insects, and scarce water on the trail. Hostile Indians also threatened riders as well as station keepers. Not surprisingly, Pony Express riders were revered as heroes and many became legends in their own time. Among the most famous is probably William (“Buffalo Bill”) Cody, whose legend included a nearly continuous 22-hour ride in Wyoming from Red Butte Station to Pacific Springs and back, a distance of some 300 mile.

Once the transcontinental telegraph line was completed in October 1861, the demise of the Pony Express was imminent. Not only was it no longer viewed as a necessity, it was also falling out of favor with the public, most of which could not afford to utilize the service. It was also a money pit, costing some $1,000 per day to operate. Its total costs were $700,000; its total receipts were about $500,000. Two days after the telegraph wires were connected on October 24, 1861, the Pony Express announced its closure.

Still, the Pony Express is ranked among the most remarkable feats of the American West. During its 18 months of operation, the Pony Express made a total of 308 complete runs, covering a distance of about 616,000 miles—equivalent to circling Earth more than 30 times.

The annual re-ride celebrating the history of the Pony Express normally takes place within the first two weeks of June, and coincides with the full moon so night riders have moonlight to light their way. The re-ride alternates from east to west and west to east each year. The Pony Riders travel day and night to make the 10 day trip. This year, the ride is scheduled to end on June 17 in St. Joseph, Missouri. You can also follow along thanks a GPS tracker carried in the mochila, which pings every five minutes to mark a Pony Rider location. Check it out HERE. Learn more about the annual re-ride, including how you can participate, at the National Pony Express Association.